Induced representation

In mathematics, and in particular group representation theory, the induced representation is one of the major general operations for passing from a representation of a subgroup H to a representation of the (whole) group G itself. It was initially defined as a construction by Frobenius, for linear representations of finite groups. It includes as special cases the action of G on the cosets G/H by permutation, which is the case of the induced representation starting with the trivial one-dimensional representation of H. If H = {e} this becomes the regular representation of G. Therefore induced representations are rich objects, in the sense that they include or detect many interesting representations. The idea is by no means limited to the case of finite groups, but the theory in that case is particularly well-behaved.

Contents |

Alternate formulations

The central theorem in the finite group case is the Frobenius reciprocity theorem. It is stated in terms of another construction of representations, the restriction map (which is a functor): any linear representation of G, as K[G]-module where K[G] is the group ring of G over a field K, is also a K[H]-module. The theorem states that, given representations ρ of G and σ of H, the space of G-equivariant linear maps from ρ to Ind(σ) has the same dimension as that of the H-equivariant linear maps from Res(ρ) to σ. (Here Res stands for restricted representation, and Ind for induced representation.) It is useful (in the typical case of non-modular representations, anyway - say with K = C) for computing the decomposition of the induced representation: we can do calculations on the side of H, which is the 'small' group.

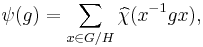

The Frobenius formula states that if χ is the character of the representation σ, given by χ(h) = Tr σ(h), then the character ψ of the induced representation is given by

where  is defined to be χ on H and 0 off H.

is defined to be χ on H and 0 off H.

Frobenius reciprocity shows that Res and Ind are adjoint functors. More precisely, Ind is the left adjoint to Res. But in the finite group case, it is also a right adjoint, so (Res, Ind) is a Frobenius pair. The content of that statement is more than the dimensions: it requires that the isomorphism of vector spaces of intertwining maps be natural, in the sense of category theory. It actually suggests that induced representation can in this case be defined by means of the adjunction. That's not the only way to do it - and perhaps not the only helpful way - but it means that the theory will not be ad hoc in its start.

One can therefore make the reciprocity theorem the way to define the induced representation. There is another way, suggested by the permutation examples of the introductory paragraph. The induced representation Ind(σ) should be realized as a space of functions on G transforming under H according to the representation σ. Therefore if σ acts on the vector space V, we should look at V-valued functions on G on which H acts via σ (this must be said carefully with explicit talk about left- and right-actions). This approach allows the induced representation to be a kind of free module construction.

The two approaches outlined above can be reconciled in the case of finite groups, by using the tensor product with K[G] as a K[H]-module. There is a third and classical approach, of simply writing down the character (trace) of the induced representation, in terms of conjugation in G of elements g into H.

The reciprocity formula can sometimes be generalized to more general topological groups; for example, the Selberg trace formula and the Arthur-Selberg trace formula are generalizations of Frobenius reciprocity to discrete cofinite subgroups of certain locally compact groups.

Construction

Algebraic

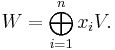

Let G be a finite group and H any subgroup of G. Furthermore let (π,V) be a representation of H. Let n = [G:H] and let x1, …, xn be a full set of representatives in G of the cosets in G/H. The induced representation  can be thought of as acting on the following space:

can be thought of as acting on the following space:

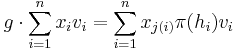

Here each xi V is an isomorphic copy of the vector space V. For each g in G and each xi there is an h = hi in H and j = j(i) in { 1, …, n } such that gxi = xjh. This is just another way of saying that x1, …, xn is a full set of representatives. Via the induced representation G acts on W as follows:

where  for each

for each  .

.

As mentioned earlier this construction is equivalent to defining ![\operatorname{Ind}_H^G \pi = K[G] \otimes_{K[H]} V.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/16dee98b80a6dd692724b8d50cdbb89e.png)

Analytic

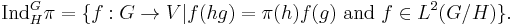

If G is a locally compact topological group (possibly infinite) and H is a closed subgroup then there is a common analytic construction of the induced representation. Let (π,V) be a continuous representation of H into a Hilbert space V. We can then let:

Here L2(G) is taken with respect to a Haar measure. The group G acts on the induced representation space by right translation, that is, (g·f)(x) = f(xg).

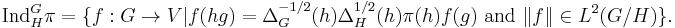

This construction is often modified in various ways to fit the applications needed. A common version is called normalized induction and usually uses the same notation. The definition of the representation space is as follows:

Here ΔG and ΔH are the modular functions of G and H respectively. With the addition of the normalizing factors this induction functor takes unitary representations to unitary representations.

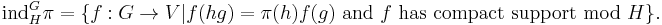

One other variation on induction is called compact induction. This is just standard induction restricted to functions with compact support. Formally it is denoted by ind and defined as:

Note that if G/H is compact then Ind and ind are the same functor.

Geometric

Suppose G is a topological group and H is a closed subgroup of G. Also, suppose σ is a realization of H over the space V. The product V×G is a realization of G as follows:

- g′[(x,g)]=(x,gg′−1)

where g and g′ are elements of G and x is an element of V.

Define the equivalence relation

- (x,g)~(h[x],hg).

Note that this equivalence relation is invariant under the action of G. In other words, V×G/~ is a realization of G.

- g−1hg[(x,g)]=(x,h−1g)~(h[x],g)

In other words, V×G/~ is a fiber bundle over the quotient space G/H with H as the structure group and V as the fiber.

Now suppose σ is a representation and V is a vector space. The previous construction defines a vector bundle over G/H. The space of sections of this vector bundle is the induced representation.

In the case of unitary representations of locally compact groups, the induction construction can be formulated in terms of systems of imprimitivity.

Examples

For any group, the induced representation of the trivial representation of the trivial subgroup is the right regular representation. More generally the induced representation of the trivial representation of any subgroup is the permutation representation on the cosets of that subgroup.

An induced representation of a one dimensional representation is called a monomial representation, because it can be represented as monomial matrices. Some groups have the property that all of their irreducible representations are monomial, the so-called monomial groups.

In Lie theory, an extremely important example is parabolic induction: inducing representations of a reductive group from representations of its parabolic subgroups. This leads, via the philosophy of cusp forms, to the Langlands program.

See also

References

- Alperin, J.L.; Rowen B. Bell (1995). Groups and Representations. Springer-Verlag. pp. 164–177. ISBN 0-387-94526-1.